Entries Tagged 'Article' ↓

August 19th, 2010 — Article, Style Inspiration

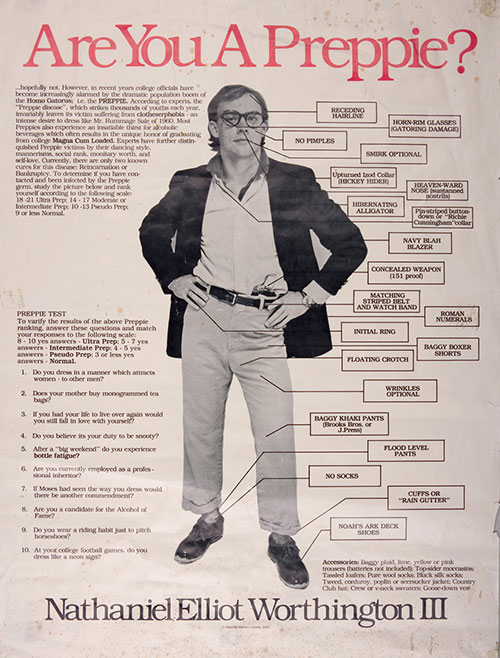

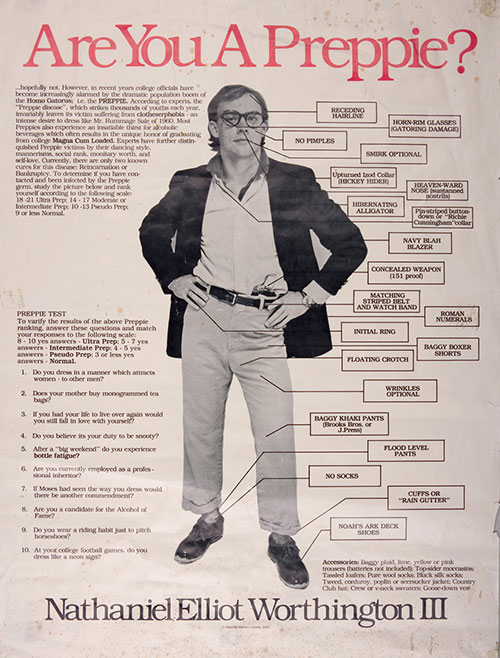

Fashion Rules

We know that many of you understand the principles of preppy style. But just to be sure, let’s review them again.

We wear sportswear. This makes it easier to go from sporting events to social events (not that there is much difference) without changing.

We generally underdress. We prefer it to overdressing.

Your underwear must not show. Wear a nude-colored strapless bra. Pull up your pants. Wear a belt. Do something. Use a tie!

We do not display our wit through T-shirt slogans.

Every single one of us—no matter the age or gender or sexual preference—owns a blue blazer.

We take care of our clothes, but we’re not obsessive. A tiny hole in a sweater, a teensy stain on the knee of our trousers, doesn’t throw us. (We are the people who brought you duct-taped Blucher moccasins.)

We do, however, wear a lot of white in the summer, and it must be spotless.

Don’t knock seersucker till you’ve tried it. (Between Memorial Day and Labor Day, unless you live in Palm Beach or Southern California, or the southern Mediterranean, please.)

Bags and shoes need not match.

Jewelry should not match, though metals should.

On the other hand, your watch doesn’t have to be the same metal as your jewelry.

And you can wear gold with a platinum wedding band and/or engagement ring.

Men’s jewelry should be restricted to a handsome watch, a wedding band if he is American and married, and nothing else. If he has a family-crest ring, it may be worn as well. For black-tie, of course, shirt studs and matching cuff links are de rigueur.

Nose rings are never preppy.

Neither (shudder) are belly-button piercings.

Nor are (two shudders) tongue studs.

And that goes for ankle bracelets.

Tattoos: Men who have been in a war have them, and that’s one thing. (Gang wars don’t count.) Anyone else looks like she is trying hard to be cool. Since the body ages, if you must tattoo, find a spot that won’t stretch too much. One day you will want to wear a halter-necked backless gown. Will you want everyone at the party to know you once loved John Krasinski?

Sneakers (a.k.a. tennis shoes, running shoes, trainers) are not worn with skirts.

Men may wear sneakers with linen or cotton trousers to casual summer parties.

Women over the age of 15 may wear a simple black dress. Women over the age of 21 must have several in rotation.

High-heel rule: You must be able to run in them—on cobblestones, on a dock, in case of a spontaneous foot race.

Clothes can cost any amount, but they must fit. Many a preppy has an item from a vintage shop or a lost-and-found bin at the club that was tailored and looks incredibly chic.

Do not fret if cashmere is too pricey. Preppies love cotton and merino-wool sweaters.

We do not wear our cell phones or BlackBerrys suspended from our belts. (That includes you, President Obama.)

Real suspenders are attached with buttons. We do not wear the clip versions.

Learn how to tie your bow tie. Do not invest in clip-ons.

Preppies are considerate about dressing our age. It is for you, not for us.

Men, if you made the mistake of buying Tevas or leather sandals, please give them to Goodwill.

You may, however, wear flip-flops to the beach if your toes are presentable. Be vigilant!

Pareos (sarongs) are for the beach, not for the mall. (Even if it’s near the beach.)

Riding boots may be worn by non-riders; cowboy boots may be worn by those who have never been on a horse. However, cowboy hats may not be worn by anyone who isn’t technically a cowboy or a cowgirl.

You may wear a Harvard sweatshirt if: you attended Harvard, your spouse attended Harvard, or your children attend Harvard. Otherwise, you are inviting an uncomfortable question.

If your best friend is a designer (clothes, accessories, jewelry), you should wear a piece from his or her collection. If his or her taste and yours don’t coincide, buy a piece or two to show your loyal support—but don’t wear them.

Every preppy woman has a friend who is a jewelry designer.

No man bags.

Preppies don’t perm their hair.

Preppy men do not believe that comb-overs disguise anything.

You can never go wrong with a trench coat.

Sweat suits are for sweating. You can try to get away with wearing sweats to carpool, to pick up the newspaper, or to drive to the dump, but last time you were at the dump, the drop-dead-attractive widower from Maple Lane was there, too.

And finally:

The best fashion statement is no fashion statement. – Vanity Fair.Com

Click Here to Continue Reading “The Official Preppy Reboot”

August 2nd, 2010 — Article, Eco Friendlly, The Husband, Wedding

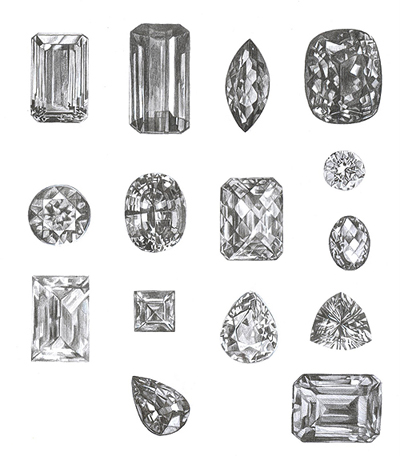

What are conflict diamonds, sometimes called blood diamonds?

Conflict diamonds, sometimes called blood diamonds, are diamonds that are sold to fund the unlawful and illegal operations of rebel, military and terrorist groups. Countries that have been most affected by conflict diamonds are Sierra Leone, Angola, Liberia and the Democratic Republic of Congo — all places where citizens have been terrorized, mutilated and killed by groups in control of the local diamond trade.

Wars in most of those areas have ended or at least decreased in intensity, but conflict diamonds from Côte d’Ivoire, in West Africa, and Liberia are still reaching the trade labeled as conflict-free diamonds.

In 2000, South African countries with a legitimate diamond trade began a campaign to track the origins of all rough diamonds, attempting to put a stop to blood diamond sales from known conflict areas. Their efforts eventually resulted in The Kimberley Process Certification Scheme (KPCS), an international effort to rid the world of conflict diamonds.

Kimberley Process Goals

The goals of the Kimberley Process are to document and track all rough diamonds entering a participating country, with shippers placing stones in tamper-proof shipping crates and providing enough detailed information about their origins to prove they did not originate in a conflict zone.

The KPCS isn’t fully operational among its members — probably normal for an agreement that involves the cooperation of dozens of governments and non-governmental agencies. Many countries haven’t even committed to the program.

The goals of the KPCS will take time to achieve, but what’s already been accomplished is significant. Because it’s a self-regulating program, additional controls are necessary to truly ensure that blood diamond trade is halted — or at least minimized.

How consumers can help stop blood diamond trade.

Retailers cannot guarantee that the diamond you purchase is not a conflict diamond. As consumers, we have the power to change that by demanding details about the diamonds we buy. Demanding proof that a diamond is conflict-free sends a powerful message to the world that we will not support an industry or nation that helps fund terror groups. Change won’t happen overnight, but it will happen if we are persistent.

Canadian diamonds – the Code of Conduct

Canada has made progress in identifying diamonds originating in its mines. The Voluntary Code of Conduct for Authenticating Canadian Diamond Claims sets a standard for authentication of claims that a diamond is Canadian — and conflict free.

Adhering to The Code requires each company to initiate a paper trail that tracks a diamond’s progression from the mine to its retail destination. The Code also includes rules for proper handling, packing and marking of all diamonds that are represented as Canadian stones. Even with the guidelines, there’s no way to absolutely guarantee a diamond is Canadian, but the process definitely helps eliminate doubt.

The Canadian program is voluntary, so not all retailers participate. Those who do must provide consumers with:

- The diamond Identification Number

- The retailer’s name and address

- An invoice number and the date of the invoice

- The polished diamond description

- An explanation of the Code

A list of signatories of the Code is available online, naming retailers and wholesalers who are committed to following the Code’s procedures.

It’s difficult for most of us to imagine what life is like in countries where diamonds are the source of so much chaos and suffering, and the connection between terror and diamonds is not something that’s reported heavily in the press. The 2006 movie Blood Diamond, starring Leonardo DiCaprio, should help make the issues more mainstream, if only temporarily.

Take some time to learn more about the problems that conflict diamonds create, then follow your heart the next time you shop for a diamond. – About.Com

August 2nd, 2010 — Article, Gifts, The Husband, Wedding

Turns out diamonds may not be everyone’s best friend. The United States buys $25 billion worth of the gems each year — as much as the rest of the world’s countries combined. But the profits don’t always go to the people who mine, cut, and polish the stones. Often they go to finance warfare, as seen in the movie Blood Diamond, starring January cover girl Jennifer Connelly. A blood, or conflict, diamond is one mined in an African war zone, then sold to a supplier to finance rebel warfare. And yet buying a “clean” diamond can be difficult because it’s often impossible to track its origin.

Diamonds have a long history of being one of the most valuable commodities in Africa, beginning in 1866, when the stones were discovered in South Africa. (In 1870, 269,000 carats were extracted from South Africa; by 2006, the number had risen to about 10 million carats annually.) With subsequent diamond discoveries in other parts of Africa, the rush that followed began a complex story of corruption. It’s counterintuitive that the existence of a rich natural resource could hurt, rather than help, the economy, and become a source of violence and bloodshed. But since the early 1990s, rebel groups in Sierra Leone, Angola, and other countries have controlled the mines, coercing workers to labor in them and fund warfare. Rapper Kanye West brought attention to the problem with his 2005 song, “Diamonds from Sierra Leone”: “The diamonds, the chains, the bracelets, the charmses/I thought my Jesus Piece was so harmless/’til I seen a picture of a shorty armless.”

In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), about one million diamond diggers work for less than a dollar per day. The majority of the operations involve alluvial mining: People, including children, stand in a stream with a sieve or other simple tool, sifting through dirt and working inhumane hours under grim conditions with no guarantee they’ll find anything. And while the DRC has 30 percent of the world’s diamond reserves and produces $2 billion worth of diamonds annually, 90 percent of its population lives in poverty. Even more devastating: Since 1998, four million people in the DRC have died in civil war conflicts.

“It’s diamonds for guns,” explains Beth Gerstein, 31, who, in December of 2004, was about to get engaged when she and her boyfriend saw a PBS Frontline report on conflict diamonds. Conflict diamonds can enter the trade when rebels smuggle the diamonds across the borders into “conflict-free” zones, where they are sold to the international market. Money made from these sales is then used to buy arms for rebel militias in countries like Sierra Leone. “We didn’t want this symbol of our commitment and love to be implicated in the suffering of others,” she says. But most of the jewelers they approached claimed they didn’t know the issues. “When we’d ask, ‘Where does this diamond come from?’ they said they couldn’t tell us. They said, ‘Trust us, it’s not a problem.'”

In theory, it shouldn’t be a problem. In 2003, the United Nations passed the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme, wherein countries agree to voluntarily monitor their diamond supplies to ensure they’re not financing rebel militias. Most of the larger diamond companies have reported drops in the rate of conflict stones in their supplies since Kimberley — saying that less than 1% of the gems on the market are conflict diamonds, according to the World Diamond Council — but Amnesty International points out that change is slower than people may think. In a September 2006 survey of jewelry retailers, only 27% said they had a policy on conflict diamonds; and of those, only half issued warranties. Many were unable to explain the conflict-diamond crisis and were unaware of the Kimberley Process. Furthermore, 110 out of 246 shops across the U.S. refused outright to take the survey.

“There’s a vast imbalance between public relations effort and the effort made to ensure that the Kimberley Process is really working,” says Amy O’Meara, an associate with the Business and Human Rights program for Amnesty International USA. The Kimberley Process is self-regulated, so it’s difficult to trust. Those in charge of monitoring are also the people who stand to profit from the diamonds. “The industry has agreed to police itself. While we’re happy they made that commitment, they have a lot of history to overcome,” O’Meara says.

Gerstein thinks people should take matters into their own hands. “The industry is only going to change if consumers demand it,” she says. Which is why she co-founded Brilliant Earth, a company that sells only conflict-free diamonds — mining them from Canada, where a third party regulates, monitors, and tracks the gems. She also co-founded Diamonds for Africa Fund (DFA), a nonprofit that provides medicine, food, and books to African communities ravaged by unethical mining.

No matter where you’re shopping for diamonds, you can always put your mind at ease by asking the following questions (from Amnesty International USA’s diamond buying guide), which any diamond salesperson should be able to answer:

- How can I be sure none of your jewelry contains conflict diamonds?

- Do you know where the diamonds you sell come from?

- Can I see a copy of your company’s policy on conflict diamonds?

- Can you show me a written statement from your suppliers guaranteeing that your diamonds are conflict-free?

“Keep asking questions until you feel comfortable,” advises O’Meara. Go to brilliantearth.com to get more information; visit diamondsforafricafund.org to donate; or log on to amnestyusa.org to find out how you can put pressure on the diamond industry. – MarieClaire.Com

July 30th, 2010 — Advice, Article

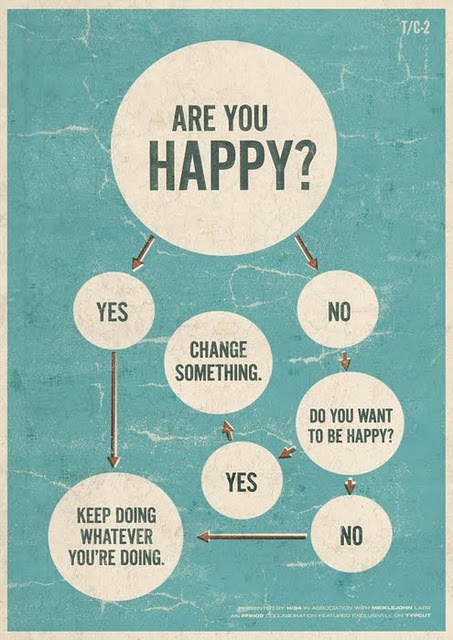

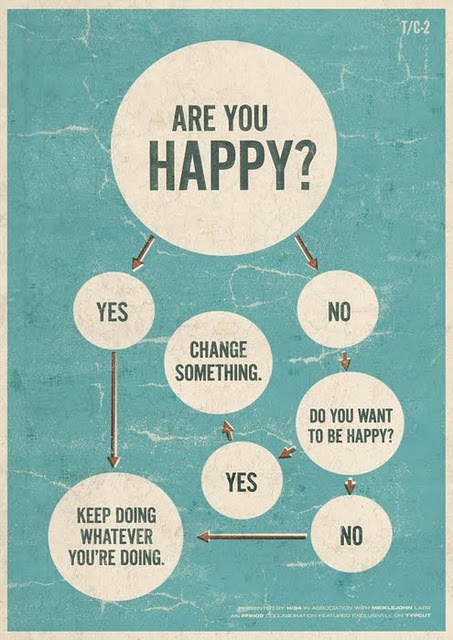

The Return of The Happy Housewife

March 5, 2006 By: Charlotte Allen for The Los Angeles Times

BETTY FRIEDAN, it seems, died just in time to roll over in her grave.

A new study by two University of Virginia sociologists concludes that stay-at-home wives whose husbands are the primary family breadwinners don’t suffer from “the problem that has no name,” as Friedan famously wrote in 1963. In fact, the majority of full-time homemakers don’t experience any kind of special problem, according to professors W. Bradford Wilcox and Stephen L. Nock, who analyzed data from a huge University of Wisconsin survey of families, conducted during the 1990s.

Here are the figures, published in this month’s issue of the journal Social Forces: 52% of wives who don’t work outside the home reported they were “very happy” with their marriages, compared with 41% of wives in the workforce.

The more traditional a marriage is, the sociologists found, the higher the percentage of happy wives. Among couples who have the husband as the primary breadwinner, who worship together regularly and who believe in marriage as an institution that requires a lifelong commitment, 61% of wives said they were “very happy” with their marriages. Among couples whose marriage does not have all these characteristics, the percentage of happy wives dips to an average of 45.

Lest you think the statistics come out this way because tradition-minded women happen to like tradition-minded wedlock — or they’re just brainwashed by their churches — you’re wrong. In an unpublished second paper, Wilcox sifted through the survey data and discovered that even wives who describe themselves as feminists report being happier with traditional marital arrangements in which they stay home with the kids and their husbands provide for them.

“They might think of themselves as progressives and believe in gender equality, but the same pattern holds for them,” Wilcox said.

One more surprise: Even for wives who work full time outside the home, the key to marital happiness isn’t splitting household chores and child care down the middle with their husbands. It’s much simpler: an affectionate and appreciative husband who believes, along with his wife, that marriage is forever. Sociologists call it “emotion work” — husbands talking to their wives, being understanding and supportive, spending quality time in the form of romantic evenings for two, walking hand-in-hand on the beach and so forth.

“It’s far more important than who does the dishes and folds the laundry,” Wilcox said.

Continue Reading

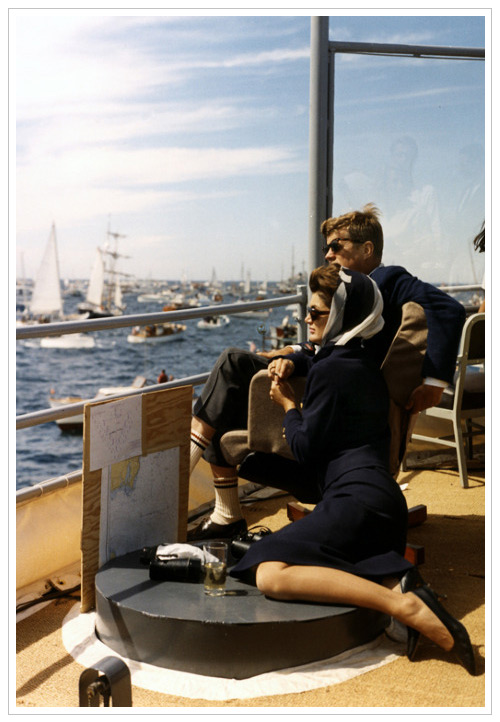

June 25th, 2010 — Article, Health

By: Tara Parker -Pope for The New York Times

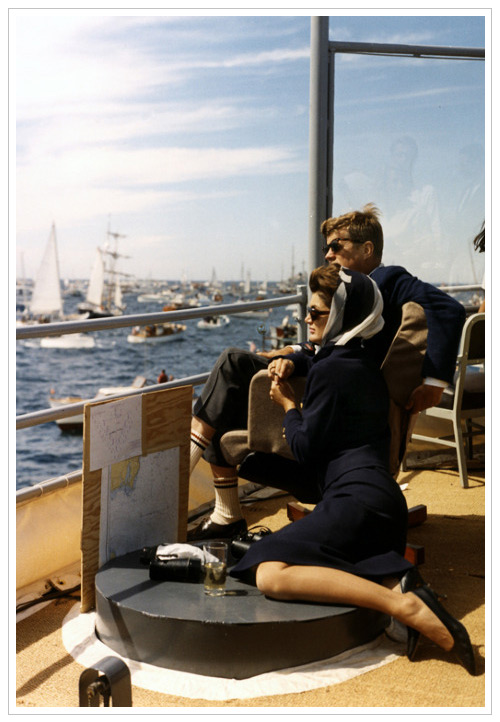

In 1858, a British epidemiologist named William Farr set out to study what he called the “conjugal condition” of the people of France. He divided the adult population into three distinct categories: the “married,” consisting of husbands and wives; the “celibate,” defined as the bachelors and spinsters who had never married; and finally the “widowed,” those who had experienced the death of a spouse. Using birth, death and marriage records, Farr analyzed the relative mortality rates of the three groups at various ages. The work, a groundbreaking study that helped establish the field of medical statistics, showed that the unmarried died from disease “in undue proportion” to their married counterparts. And the widowed, Farr found, fared worst of all.

Farr’s was among the first scholarly works to suggest that there is a health advantage to marriage and to identify marital loss as a significant risk factor for poor health. Married people, the data seemed to show, lived longer, healthier lives. “Marriage is a healthy estate,” Farr concluded. “The single individual is more likely to be wrecked on his voyage than the lives joined together in matrimony.”

While Farr’s own study is no longer relevant to the social realities of today’s world — his three categories exclude couples living together, gay couples and the divorced, for instance — his overarching finding about the health benefits of marriage seems to have stood the test of time. Critics, of course, have rightly cautioned about the risk of conflating correlation with causation. (Better health among the married sometimes simply reflects the fact that healthy people are more likely to get married in the first place.) But in the 150 years since Farr’s work, scientists have continued to document the “marriage advantage”: the fact that married people, on average, appear to be healthier and live longer than unmarried people.

Contemporary studies, for instance, have shown that married people are less likely to getpneumonia, have surgery, develop cancer or have heart attacks. A group of Swedish researchers has found that being married or cohabiting at midlife is associated with a lower risk for dementia. A study of two dozen causes of death in the Netherlands found that in virtually every category, ranging from violent deaths like homicide and car accidents to certain forms of cancer, the unmarried were at far higher risk than the married. For many years, studies like these have influenced both politics and policy, fueling national marriage-promotion efforts, like the Healthy Marriage Initiative of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. From 2006 to 2010, the program received $150 million annually to spend on projects like “divorce reduction” efforts and often cited the health benefits of marrying and staying married.

But while it’s clear that marriage is profoundly connected to health and well-being, new research is increasingly presenting a more nuanced view of the so-called marriage advantage. Several new studies, for instance, show that the marriage advantage doesn’t extend to those in troubled relationships, which can leave a person far less healthy than if he or she had never married at all. One recent study suggests that a stressful marriage can be as bad for the heart as a regular smoking habit. And despite years of research suggesting that single people have poorer health than those who marry, a major study released last year concluded that single people who have never married have better health than those who married and then divorced.

All of which suggests that while Farr’s exploration into the conjugal condition pointed us in the right direction, it exaggerated the importance of the institution of marriage and underestimated the quality and character of the marriage itself. The mere fact of being married, it seems, isn’t enough to protect your health. Even the Healthy Marriage Initiative makes the distinction between “healthy” and “unhealthy” relationships when discussing the benefits of marriage. “When we divide good marriages from bad ones,” says the marriage historian Stephanie Coontz, who is also the director of research and public education for the Council on Contemporary Families, “we learn that it is the relationship, not the institution, that is key.”

Continue Reading