Entries Tagged 'The Husband' ↓

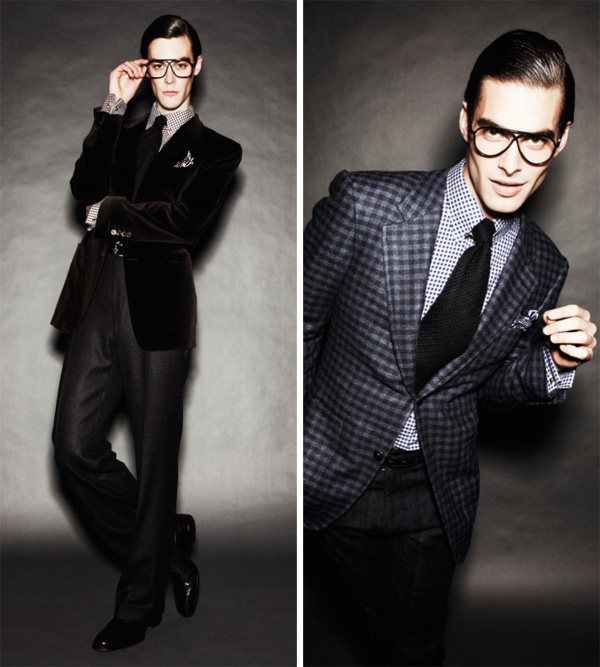

The Husband: Tom Ford, Fall 2010

August 5th, 2010 — The Husband

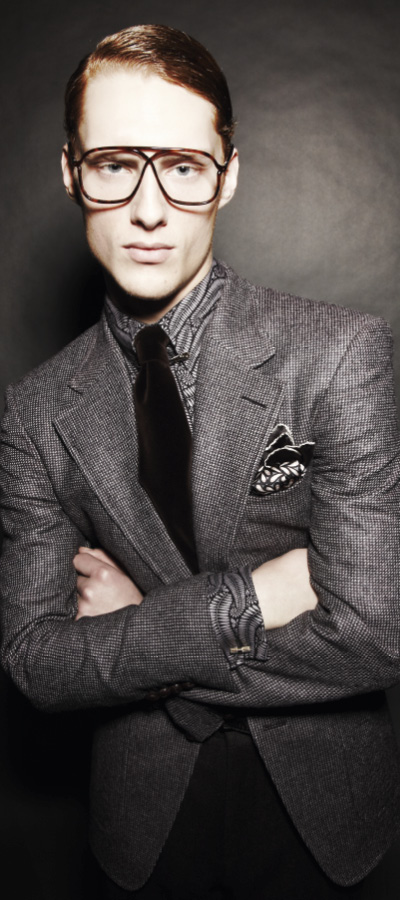

The Modern Voice of Classic Men’s Elegance: THE RAKE

August 4th, 2010 — The Husband, Things I Love

At once responding to and actively promoting a renaissance in gentlemanly sophistication and style, The Rake meets the needs of a disenfranchised, elite (yet expansive) sector of the male population – one seeking to recapture the codes of classic men’s elegance.

Catering to the reader alienated by ‘edgy’ men’s fashion magazines and insufficiently served by major male lifestyle titles, The Rake is aimed at the mature-minded gent who draws his sartorial inspiration from icons such as Cary Grant, Fred Astaire, the Duke of Windsor, Gianni Agnelli and Sean Connery, and their contemporary counterparts.

The Rake’s priority is to provide a precise framework for classically elegant dressing. The magazine spells out, in exquisite detail, the ground-rules for grand, flattering dressing…and then explains how and when those rules may be broken.

Though clothing is central to the magazine’s vision, it is The Rake’s firm belief that true elegance comes from within. Thus, our goal is to not only provide readers with informative, incisive, in-depth commentary on matters of attire, but also, the many elements of gentlemanly conduct and living. From manners and ethics, to art and design, tasteful travel, health and well-being, the intellectual and philosophical, to homes, modes of transport, entertainment, food and drink, The Rake’s purview encompasses the full spectrum of elegant living.

Husband with Style: Oscar De La Renta

August 4th, 2010 — The Husband

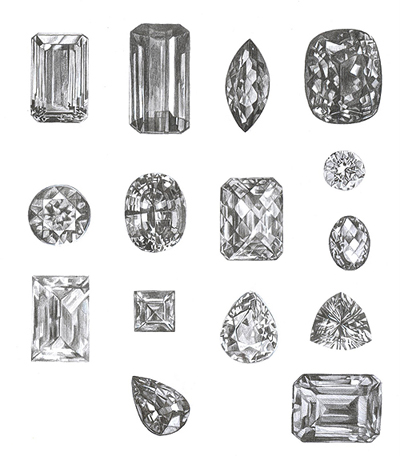

How to Buy Conflict Free Diamonds

August 2nd, 2010 — Article, Eco Friendlly, The Husband, Wedding

What are conflict diamonds, sometimes called blood diamonds?

Conflict diamonds, sometimes called blood diamonds, are diamonds that are sold to fund the unlawful and illegal operations of rebel, military and terrorist groups. Countries that have been most affected by conflict diamonds are Sierra Leone, Angola, Liberia and the Democratic Republic of Congo — all places where citizens have been terrorized, mutilated and killed by groups in control of the local diamond trade.

Wars in most of those areas have ended or at least decreased in intensity, but conflict diamonds from Côte d’Ivoire, in West Africa, and Liberia are still reaching the trade labeled as conflict-free diamonds.

In 2000, South African countries with a legitimate diamond trade began a campaign to track the origins of all rough diamonds, attempting to put a stop to blood diamond sales from known conflict areas. Their efforts eventually resulted in The Kimberley Process Certification Scheme (KPCS), an international effort to rid the world of conflict diamonds.

Kimberley Process Goals

The goals of the Kimberley Process are to document and track all rough diamonds entering a participating country, with shippers placing stones in tamper-proof shipping crates and providing enough detailed information about their origins to prove they did not originate in a conflict zone.

The KPCS isn’t fully operational among its members — probably normal for an agreement that involves the cooperation of dozens of governments and non-governmental agencies. Many countries haven’t even committed to the program.

The goals of the KPCS will take time to achieve, but what’s already been accomplished is significant. Because it’s a self-regulating program, additional controls are necessary to truly ensure that blood diamond trade is halted — or at least minimized.

How consumers can help stop blood diamond trade.

Retailers cannot guarantee that the diamond you purchase is not a conflict diamond. As consumers, we have the power to change that by demanding details about the diamonds we buy. Demanding proof that a diamond is conflict-free sends a powerful message to the world that we will not support an industry or nation that helps fund terror groups. Change won’t happen overnight, but it will happen if we are persistent.

Canadian diamonds – the Code of Conduct

Canada has made progress in identifying diamonds originating in its mines. The Voluntary Code of Conduct for Authenticating Canadian Diamond Claims sets a standard for authentication of claims that a diamond is Canadian — and conflict free.

Adhering to The Code requires each company to initiate a paper trail that tracks a diamond’s progression from the mine to its retail destination. The Code also includes rules for proper handling, packing and marking of all diamonds that are represented as Canadian stones. Even with the guidelines, there’s no way to absolutely guarantee a diamond is Canadian, but the process definitely helps eliminate doubt.

The Canadian program is voluntary, so not all retailers participate. Those who do must provide consumers with:

- The diamond Identification Number

- The retailer’s name and address

- An invoice number and the date of the invoice

- The polished diamond description

- An explanation of the Code

A list of signatories of the Code is available online, naming retailers and wholesalers who are committed to following the Code’s procedures.

It’s difficult for most of us to imagine what life is like in countries where diamonds are the source of so much chaos and suffering, and the connection between terror and diamonds is not something that’s reported heavily in the press. The 2006 movie Blood Diamond, starring Leonardo DiCaprio, should help make the issues more mainstream, if only temporarily.

Take some time to learn more about the problems that conflict diamonds create, then follow your heart the next time you shop for a diamond. – About.Com

“Cut, Color Clarity and a Clean Conscience”

August 2nd, 2010 — Article, Gifts, The Husband, Wedding

Turns out diamonds may not be everyone’s best friend. The United States buys $25 billion worth of the gems each year — as much as the rest of the world’s countries combined. But the profits don’t always go to the people who mine, cut, and polish the stones. Often they go to finance warfare, as seen in the movie Blood Diamond, starring January cover girl Jennifer Connelly. A blood, or conflict, diamond is one mined in an African war zone, then sold to a supplier to finance rebel warfare. And yet buying a “clean” diamond can be difficult because it’s often impossible to track its origin.

Diamonds have a long history of being one of the most valuable commodities in Africa, beginning in 1866, when the stones were discovered in South Africa. (In 1870, 269,000 carats were extracted from South Africa; by 2006, the number had risen to about 10 million carats annually.) With subsequent diamond discoveries in other parts of Africa, the rush that followed began a complex story of corruption. It’s counterintuitive that the existence of a rich natural resource could hurt, rather than help, the economy, and become a source of violence and bloodshed. But since the early 1990s, rebel groups in Sierra Leone, Angola, and other countries have controlled the mines, coercing workers to labor in them and fund warfare. Rapper Kanye West brought attention to the problem with his 2005 song, “Diamonds from Sierra Leone”: “The diamonds, the chains, the bracelets, the charmses/I thought my Jesus Piece was so harmless/’til I seen a picture of a shorty armless.”

In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), about one million diamond diggers work for less than a dollar per day. The majority of the operations involve alluvial mining: People, including children, stand in a stream with a sieve or other simple tool, sifting through dirt and working inhumane hours under grim conditions with no guarantee they’ll find anything. And while the DRC has 30 percent of the world’s diamond reserves and produces $2 billion worth of diamonds annually, 90 percent of its population lives in poverty. Even more devastating: Since 1998, four million people in the DRC have died in civil war conflicts.

“It’s diamonds for guns,” explains Beth Gerstein, 31, who, in December of 2004, was about to get engaged when she and her boyfriend saw a PBS Frontline report on conflict diamonds. Conflict diamonds can enter the trade when rebels smuggle the diamonds across the borders into “conflict-free” zones, where they are sold to the international market. Money made from these sales is then used to buy arms for rebel militias in countries like Sierra Leone. “We didn’t want this symbol of our commitment and love to be implicated in the suffering of others,” she says. But most of the jewelers they approached claimed they didn’t know the issues. “When we’d ask, ‘Where does this diamond come from?’ they said they couldn’t tell us. They said, ‘Trust us, it’s not a problem.'”

In theory, it shouldn’t be a problem. In 2003, the United Nations passed the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme, wherein countries agree to voluntarily monitor their diamond supplies to ensure they’re not financing rebel militias. Most of the larger diamond companies have reported drops in the rate of conflict stones in their supplies since Kimberley — saying that less than 1% of the gems on the market are conflict diamonds, according to the World Diamond Council — but Amnesty International points out that change is slower than people may think. In a September 2006 survey of jewelry retailers, only 27% said they had a policy on conflict diamonds; and of those, only half issued warranties. Many were unable to explain the conflict-diamond crisis and were unaware of the Kimberley Process. Furthermore, 110 out of 246 shops across the U.S. refused outright to take the survey.

“There’s a vast imbalance between public relations effort and the effort made to ensure that the Kimberley Process is really working,” says Amy O’Meara, an associate with the Business and Human Rights program for Amnesty International USA. The Kimberley Process is self-regulated, so it’s difficult to trust. Those in charge of monitoring are also the people who stand to profit from the diamonds. “The industry has agreed to police itself. While we’re happy they made that commitment, they have a lot of history to overcome,” O’Meara says.

Gerstein thinks people should take matters into their own hands. “The industry is only going to change if consumers demand it,” she says. Which is why she co-founded Brilliant Earth, a company that sells only conflict-free diamonds — mining them from Canada, where a third party regulates, monitors, and tracks the gems. She also co-founded Diamonds for Africa Fund (DFA), a nonprofit that provides medicine, food, and books to African communities ravaged by unethical mining.

No matter where you’re shopping for diamonds, you can always put your mind at ease by asking the following questions (from Amnesty International USA’s diamond buying guide), which any diamond salesperson should be able to answer:

- How can I be sure none of your jewelry contains conflict diamonds?

- Do you know where the diamonds you sell come from?

- Can I see a copy of your company’s policy on conflict diamonds?

- Can you show me a written statement from your suppliers guaranteeing that your diamonds are conflict-free?

“Keep asking questions until you feel comfortable,” advises O’Meara. Go to brilliantearth.com to get more information; visit diamondsforafricafund.org to donate; or log on to amnestyusa.org to find out how you can put pressure on the diamond industry. – MarieClaire.Com